Long Barrows and Broken Bones

What the atmospheric, evocative long barrows of the Cotswold Hills and Marlborough Downs reveal about burial practices and attitudes to death in the early Neolithic period.

OLDEST ARCHITECTURE

Long barrows – elongated stone monuments to the dead – belong to the oldest surviving architectural tradition in England. Between 3800 BC and 3500 BC almost every community in the Cotswold–Severn area built one. More than 150 survive, including the quaintly named Hetty Pegler’s Tump in Gloucestershire (also known as Uley Long Barrow).

Extending up to 100 metres from end to end and 20 metres across, these mounds are impressive structures, even in the modern landscape.

RITUALS AND REMAINS

Each long barrow comprises a formal trapezoidal mound of stone, with soil dug from adjacent quarries and piled high around the stone structure. A neat drystone wall around the outside contained this rubble, while at the higher and wider end of the mound there are projecting ‘horns’ defining a ‘forecourt’ in which rituals and ceremonies were played out, fires lit, and animals celebrated.

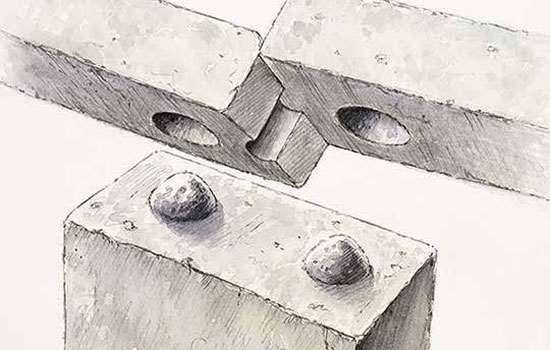

Some forecourts provide direct access to a chamber containing ancestral remains. Others have chambers accessible from the sides of the mound. In all cases these chambers were built from large stone blocks and occupied just a fraction of the area covered by the mound.

Three elements are recognisable in every chamber: a vestibule or entrance area; a passage leading into the mound; and one or more cells accessible from the passage.

WHEN WORLDS COLLIDE

How long barrows were used varied a little between communities. A common theme is that the chambers contain the broken-up remains of between five and 50 individuals – men, women and children of all ages.

Grave goods were few – just the occasional pot and selected personal ornaments. But careful excavation suggests that these barrows were opened from time to time for the addition of corpses and parts of bodies that had been stored or buried elsewhere. As the number increased it became necessary to make room for new additions by moving the remains of earlier depositions deeper into the chamber. It must have been an emotionally charged, uncomfortable experience, squeezing into the narrow spaces, moving bones about, and manoeuvring bodies into their new resting places.

Perhaps the barrows were opened at auspicious times of the year, when the boundaries between the worlds of the living and the dead were understood to be at their most permeable.

TOMBS FOR THE LIVING

Long barrows not only entombed the dead but also embodied meanings for the living that we can still dimly perceive.

Their trapezoidal form mimics that of the stone axes common at the time, for example, while forensic studies show that at least some of those interred had been killed with a blow from such an implement. The barrow-form may also represent the human torso, and placement of the dead in the darkness of the chambers might have been seen as a symbolic way of returning people to the womb, thereby completing the cycle of life.

As robust and enduring monuments, long barrows may also have been territorial markers: the physical representation of a community fixed for ever in the landscapes of the living.

Uley Long Barrow is the most evocative long barrow on the Cotswold Hills. It can be visited at any time, but take a candle in order to experience for yourself a little piece of prehistory.

Other Cotswold–Severn long barrows in the care of English Heritage include Belas Knap, Nympsfield, Windmill Tump, Rodmarton, and Notgrove, all in Gloucestershire; West Kennet, Wiltshire; Wayland’s Smithy, Oxfordshire; and Stoney Littleton, Somerset.

By Tim Darvill

Prehistory Stories

-

Food and Feasting at Stonehenge

Find out what the people who built and used Stonehenge ate, how they cooked and served their food, and the cutting-edge science behind these discoveries.

-

Long Barrows and Broken Bones

What the atmospheric, evocative long barrows of the Cotswold Hills and Marlborough Downs reveal about burial practices and attitudes to death in the early Neolithic period.

-

Building Stonehenge

Stonehenge is a masterpiece of engineering. How did Neolithic people build it using only the simple tools and technologies available to them?

-

Making Connections: Stonehenge in its Prehistoric World

At the time of Stonehenge, people connected with others and with the world around them by making and sharing objects. Explore the story of these connections.

-

Ritual Mysteries in a Prehistoric Flint Mine

What finds at Grime’s Graves in Norfolk reveal about the significance of mining, and the value of flint, to Neolithic communities.

-

Iron Age Kings and their Roman Connections

How burial goods from Essex provide tantalising glimpses of rich and powerful leaders in Iron Age Britain, and their strong links with the Roman world.

-

Roman Invasion at Maiden Castle

Britain’s largest Iron Age hillfort was once regarded as a monument to the brutality of Roman invasion, but its story may be rather more complicated.

-

Prehistoric Earthworks and Their Afterlife at Knowlton

How a unique group of Neolithic monuments in Dorset have remained a significant and atmospheric presence for 4,000 years.

More about Prehistoric England

-

Prehistoric Architecture

The structures that survive from prehistory might not be what we’d normally think of as ‘architecture’. But these structures still inspire awe today

-

Prehistoric Art

People in prehistory were skilled at making tools and decorative objects from stone and metal, sometimes with astonishing decoration.

-

Prehistoric Commerce

Goods and skills must have been bartered or exchanged in prehistoric Britain from early times, but very little evidence has survived and commece as we think of it may not have existed.

-

Prehistoric Daily Life

The arrival of farming from about 4000 BC had a profound effect on every aspect of daily life for the people who lived in the British Isles.

-

Prehistory: Landscape

How Neolithic people linked complexes of person-made monuments into artificial landscapes.

-

Prehistory: Networks

The arrival of farming, the building of great communal monuments and the knowledge of metalworking all transformed prehistoric Britain.

-

Prehistory: Power and Politics

Power in prehistoric Britain was expressed symbolically, through the likes of mighty communal monuments, rich grave goods, and massive hillforts.

-

Prehistory: Religion

There was no single or continuously developed belief system in prehistoric Britain, but we can make informed guesses about what different prehistoric people believed.

-

Prehistory: Conflict

Violence and conflict undoubtedly occurred in prehistoric Britain, but the archaeological evidence is often subject to varying interpretations.