A NEW DYNASTY

The shrewd James I (r.1603–25), who was also James VI of Scotland (and the son of Elizabeth I’s cousin Mary, Queen of Scots), successfully conjoined the two long-warring nations of England and Scotland.

Despite threats to his reign, including the Gunpowder Plot (1605), he maintained peace at home and abroad.

James’s glamorous elder son Prince Henry died in 1612, leaving his younger son, Charles I (r.1625–49), to succeed.

This sober, ceremonious monarch was devoted to the arts and to the Anglican Church, and acutely conscious of his divine right to rule.

ROYAL DECREE AND CIVIL WAR

Impatient with parliamentary control, Charles ruled by royal decree (without Parliament) from 1629 until 1640. His subjects became increasingly exasperated by the taxes he levied on them, and by the suppression of Puritanism by William Laud, the Archbishop of Canterbury.

After the fiasco of the Bishops’ Wars with the Scots of 1639–40 (provoked by the imposition of Charles’s religious reforms), the king was forced to recall Parliament in a bid to raise money. Frustration boiled over as Charles refused to give Parliament real power in State and Church. Both sides armed themselves, and despite a widespread desire for compromise, civil war broke out in August 1642.

The civil wars and their aftermath were calamitous. They killed a far greater proportion of the populations of England, Scotland and (especially) Ireland than the First World War. Many castles were pressed into active service for the first time since the Middle Ages and many – like Scarborough in North Yorkshire – underwent epic sieges.

A KING CONDEMNED

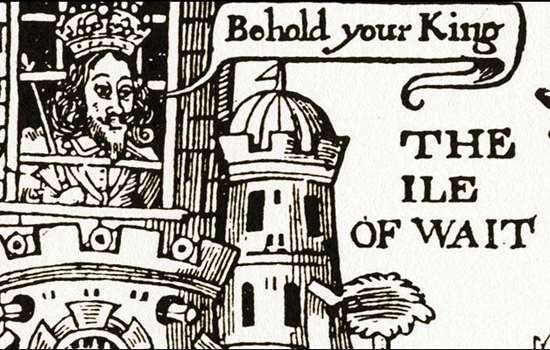

By 1647 Parliament’s New Model Army, commanded by Sir Thomas Fairfax and Oliver Cromwell, had defeated King Charles. He was imprisoned at Carisbrooke Castle on the Isle of Wight, but under the cover of peace negotiations, he secretly worked to provoke a Second Civil War, which broke out 1648. Parliament was again victorious, and this time the army accordingly insisted (despite moderate protests) on his trial, condemnation and execution in 1649.

The unprecedented public beheading of a monarch sent shockwaves through Britain and Europe. In 1651, with Scots support, the future Charles II mounted a hopeless invasion of what was now a republic, the English Commonwealth (1649–53). Defeated, he escaped to France after famously hiding in an oak tree at Boscobel in Shropshire.

THE INTERREGNUM

The period after Charles’s execution, known as the Interregnum, saw the loosening of government and Church control. In response, there was an unprecedented ferment of revolutionary ideas, which were spread by an explosion of pamphlets. Radical religious sects proliferated, many expecting the imminent Second Coming of Christ. The Levellers demanded votes for all men and universal religious tolerance.

Oliver Cromwell, who ruled as Lord Protector of the Commonwealth of England, Scotland and Ireland from 1653 until 1658, personally favoured toleration of all religions despite his own radical Puritanism. But he used military power to preserve both the fruits of his Civil War victory and national stability, commanding the confidence of both army and civil government.

At his death, this stability collapsed. Charles II was invited to return, and resumed the throne in triumph in May 1660.

RESTORATION AND REVOLUTION

Vividly chronicled in the diaries of Samuel Pepys, Charles II’s reign (1660–85) is remembered for its racy court, the revival of theatres, and new developments in art, daily life and architecture, exemplified by Sir Christopher Wren’s London churches. It also saw notable scientific advances, fostered by the Royal Society.

Following the serial disasters of the Great Plague (1665), the Great Fire of London (1666) and the humiliating Dutch raid on the Medway (1667), the latter years of Charles’s reign were dominated by attempts to exclude his openly Catholic brother James from the succession.

James II (r.1685–8) did succeed, however. His army easily defeated the rebellion (1685) of Charles’s illegitimate Protestant son, the Duke of Monmouth. But Judge Jeffreys’s brutal Bloody Assizes – the trials of the rebels – and James’s Catholicising policies made the king increasingly unpopular.

The birth of James II’s male heir made a continuation of Catholic rule more likely. A group of prominent Protestants invited James’s Dutch Protestant son-in-law, William of Orange – who was married to James’s eldest daughter, Mary – to intervene. William duly invaded in 1688, James fled, and William and Mary were crowned the following year.

SUCCESSION AND UNION

The joint rule of William III (1689–1702) and Mary II (1689–94) brought peace to England, although in Ireland and Scotland James’s supporters fought on. The Act of Settlement (1701) ensured the succession of Mary’s sister, Anne – rather than James II, his son or any other Catholic claimant – and ultimately the ‘Protestant Succession’ of the House of Hanover. This was all the more necessary since none of Anne’s 18 children reached maturity.

During Anne’s reign (1702–14) the Duke of Marlborough won famous victories against Louis XIV of France, but the most significant political event during her time on the throne was the Act of Union with Scotland (1707). For the first time, England was part of a unified Great Britain.

Stuarts Stories

-

Charles I: a Royal Prisoner at Carisbrooke Castle

Learn about Charles I’s time as a prisoner of Carisbrooke Castle on the Isle of Wight, including his many attempts to escape.

-

The Siege of Goodrich Castle

In June and July 1646, Goodrich Castle was the scene of one of the most hard-fought sieges of the Civil War.

-

Charles II and the Royal Oak

How the future king escaped from Parliamentarian forces during the Civil War in 1651, giving English history one of its greatest adventure stories.

-

Berry Pomeroy and the ‘Other’ Seymours

How an extravagant but unfinished castle tells a story of family rivalry and competitive housebuilding in 17th-century England.

-

Maritime Decline and the Battle of the Downs

How a major sea battle between the Dutch and the Spanish on the Kent coast, revealed as much about the English navy as it did about its participants.

-

The Countess of Kent and a Cookbook

One of the earliest celebrity cookbooks, includes cures for pox, plague and pestilence as well as recipes for culinary treats.

-

Border Reivers and Hadrian's Wall

How a fort, built for troops manning the frontier of Roman Britain, became a locus of crime and unrest in Stuart England.

-

Margaret Cavendish

Margaret Cavendish, Duchess of Newcastle, was one of the most prolific female authors and philosophers of the 17th century, writing at a time of immense political upheaval.

More about Stuart England

-

Stuarts: Architecture

From the grand country houses of the early Stuart period to Christopher Wren's new churches that rose from the ashes of the Great Fire of London.

-

Stuarts: Commerce

The economy of much of Stuart England was largely based on traditional industries. London, however, was at the centre of a growing international network of trade.

-

Stuarts: Parks and Gardens

The influence of the great formal gardens of the Renaissance gradually gave way to the opulence of the Baroque during the Stuart period.

-

Stuarts: War

How the reorganisation of the Parliamentary army following the devastating Civil Wars of 1642–51 was the beginning of the modern British Army tradition.

Read More

-

Previous Era: Tudors

England underwent huge changes during the reigns of three generations of Tudor monarchs. Henry VIII ushered in a new state religion, and the increasing confidence of the state coincided with the growth of a distinctively English culture.

-

Next Era: Georgians

When Queen Anne died in 1714 with no surviving children, the German Hanoverians were brought in to succeed her. This began the Georgian age – named after the first four Hanovarian kings, all called George.