1. There are over 900 ‘official’ plaques

Over 900 official plaques have been put up by in London by English Heritage and its predecessors since the scheme began in 1866.

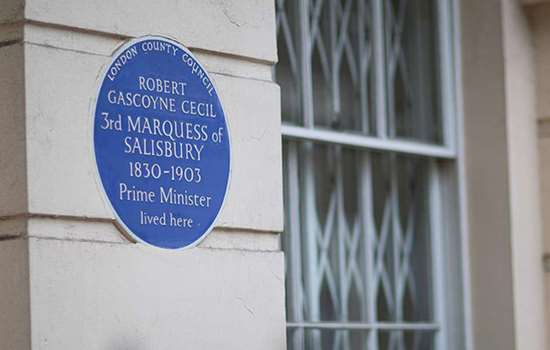

They are not always round and blue, but you can spot them by looking for the name of the organisation that erected them. The London blue plaques scheme has been run by four bodies in turn – the Society of Arts, the London County Council, the Greater London Council and now English Heritage. If you see any of these names on a plaque, then you know it’s part of the scheme.

Many other bodies, such as local councils, also put up commemorative plaques in London, using different criteria.

Find out more about other schemes2. The Oldest Surviving Plaque Goes To...

...the last French Emperor, Napoleon III, whose plaque was installed in 1867. Today, the rule is that to be awarded a plaque, a recipient must have been dead for 20 years, but Napoleon was still ruling France when his went up. The French imperial eagle is part of the plaque’s design.

Apparently Louis Napoleon left his London home in King Street, off St James’s Square, in a great hurry – his bed unmade and his bath still full of water – to return to France when he heard of the overthrow of King Louis Philippe in 1848.

Read More about Napoleon iii3. The First Plaque Was Lost to Demolition

The first blue plaque was awarded to the poet Lord Byron in 1867, but his house in Holles Street, near Cavendish Square, was demolished in 1889. A John Lewis department store occupies the site today, and bears a Westminster City Council plaque to the poet. This replaced an earlier, non-standard, plaque in 2012, which in turn succeeded a plaque lost when John Lewis was bombed in the Second World War.

Recent research has revealed that there is no clear evidence to show which house in Holles Street Byron actually lived in – raising the intriguing possibility that none of Byron’s plaques, past and present, have actually marked the correct spot.

Image © National Portrait Gallery, London

Read more about the scheme’s history4. Eighteen Houses Have Two Plaques

It’s unusual for houses in London to bear two official plaques, but there are currently 18 cases of double commemorations. Examples include 20 Maresfield Gardens (Sigmund Freud and Anna Freud) and 29 Fitzroy Square (George Bernard Shaw and Virginia Woolf).

Famously, Jimi Hendrix and George Frideric Handel have plaques on neighbouring houses in Brook Street, Mayfair. When asked about living next to Handel's old home, Hendrix is reported to have said, ‘To tell you the God's honest truth, I haven’t heard much of the fella's stuff.’

There are also some people who have more than one plaque. Mahatma Gandhi has two: one on Baron’s Court Road, West Kensington, where he lived as a law student, and the other in Powis Road, Bow. The Prime Ministers Lord Palmerston and William Gladstone each have three surviving plaques, as does the author William Makepeace Thackeray.

In recent years the rule has been only one plaque per person.

5. Plaques can help protect buildings

Because blue plaques celebrate the relationship between people and place, English Heritage only awards them if there is a close link between a person and a surviving building. In the past, some plaques marked the site of a house which had been demolished, but we now believe that if the building no longer survives, then the most meaningful connection between person and place has been lost.

Although blue plaques don’t offer legal protection to buildings, they do raise awareness of their historical significance and so can help preserve them. The homes of Oscar Wilde in Chelsea and Van Gogh in Stockwell, for instance, were preserved because of the historic associations celebrated by their blue plaques. DH Lawrence’s house, beside Hampstead Heath, is one example of a building being listed and so protected from redevelopment because of links highlighted by its plaque.

6. There are many claims to fame

Many politicians, artists, writers and scientists have received blue plaques, as you might expect. But alongside the more obvious claims to fame, many blue plaques celebrate quirkier occupations. Some of the more unusual reasons for commemoration recorded on London plaques include:

- Namer of Clouds (Luke Howard)

- Theorist of Anarchism (Prince Peter Kropotkin)

- Theatrical Wigmaker (Willy Clarkson)

- Designer of Spitalfields Silks (Anna Maria Garthwaite)

- Friend of all in Need (Mary Hughes).

The blue plaques scheme relies on public suggestions and we welcome your proposals. As long as the nomination meets our basic criteria, we’ll consider all submissions.

How to propose a plaque7. The Plaque Design Cost Four Guineas

The famous blue roundel design that we recognise today evolved over several decades – and the official plaques haven’t always been blue. The modern, simplified London plaque, however, was designed by an unnamed student of the Central School of Arts and Crafts in 1938 who was paid just four guineas.

With the addition of English Heritage’s name and portcullis logo, the same design is still in use today. Each plaque is 19 inches in diameter and is hand crafted by the artisan ceramicists, Frank and Sue Ashworth, who are based in Cornwall.

Read more about plaque designs8. The City of London has only one ‘blue plaque’

…and it isn’t blue. The terracotta plaque, commemorating Dr Samuel Johnson, was put up in 1876 by the Society of Arts, which started the scheme. It can be seen in Gough Square, just north of Fleet Street, on the outskirts of the financial district of the City of London.

Three years after it was erected it was agreed that the Corporation of the City of London would take responsibility for commemorating historic sites within its ‘square mile’, and this agreement has stood ever since.

More about the city of London scheme9. LONDON UNDERGROUND PLAQUES ARE UNIQUE

The ‘Johnston’ typeface – which was developed for London Transport in the 1930s and is still used by its successor, Transport for London – is used on four plaques associated with the London Underground.

These are:

- Edward Johnston (the master calligrapher who gave the font its name)

- Harry Beck, the designer of the ‘diagrammatic’ tube map

- Albert Henry Stanley, Lord Ashfield (‘First Chairman of London Transport’)

- Frank Pick (‘Pioneer of Good Design of London Transport’).

10. NOT ALL PLAQUES HAVE BEEN WELCOME

The plaque put up in 1937 to Karl Marx, at his final address in Chalk Farm, was taken down after it was repeatedly vandalised. Its replacement suffered the same fate and the owner of the house declined a third. The house was later demolished.

A plaque marking one of Marx’s earlier lodgings in Dean Street, Soho, was unveiled in 1967. Even then, the plaque wasn’t welcomed by some who regarded Marx as too controversial a figure to be honoured in this way. The then owner of the Quo Vadis restaurant on the ground floor of the building observed:

My clientele is the very best … rich people … nobility and royalty – and Marx was the person who wanted to get rid of them all!

More About Blue Plaques

-

Find a Blue Plaque

Discover who has been commemorated by one of the blue plaques on buildings across London.

-

Propose a Plaque

Find out how to put forward a proposal for someone you think is deserving of a London blue plaque.

-

Support the blue plaques scheme

Help secure the future of London's blue plaques scheme by making a contribution.